EDITOR'S NOTE: This column was first published in The Chronicle Herald 15 years ago, on June 6, 2004.

Was it the distant sound of thunder? Strange, though, how it never got louder or fainter and how it would not let up. It was 6 o'clock in the morning and Dad rose to investigate. His whole body was an aching reminder of the day before.

He had biked home 60 kilometres on an empty stomach after writing his high–school diploma exam in the city. By the time he hit the halfway mark, hunger and thirst had sapped all his strength. It's not as if he could stop at a corner store for a drink or a chocolate bar. He had no money. And the shops had nothing to sell, anyway. This was occupied France and everything was in short supply.

Somehow, he managed to drag himself and his bike to his mother's doorstep by evening. He drank his fill. But he was so tired that he had to have a nap even before he could contemplate a snack.

The next morning, it was the light of dawn that awoke him. But curiosity about that faraway booming sound was what brought him to his feet. Eventually, he surmised that an aerial bombardment was underway somewhere. Two hours later, by 8 o'clock, he would have his answer.

The landing and the liberation

In its French–language broadcast, the BBC announced the stunning news to everyone who had gathered in the kitchen: The Allies had landed in Normandy. As the crow flies, this was a good 200 kilometres away from the village in northern Brittany where Dad lived. Still, he could hear the rumble of the naval guns all the way down the coast.

For hearts that yearned for freedom – and for deliverance from four years of severe hardship – this was an incomprehensibly sweet sound. "Finally!" Dad exhaled, this was the long–awaited D–Day.

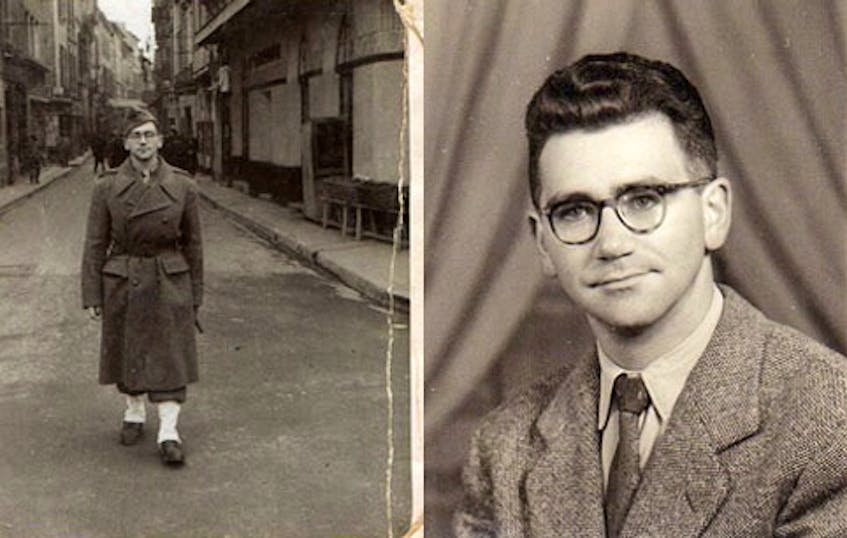

It was also his birthday. Dad had just turned 18 on that June morning like no other.

No big celebration had been planned. These were the days when kids thought getting a single orange for a Christmas present was the ultimate in luxury. The last four years had been like the last four hours of Dad's long bike ride home. It was all scarcity and perseverance.

So Dad didn't get anything for his birthday. But for D–Day, he got the gift of hope. Hope was never lost, he says, even during the darkest days of the occupation, but that morning, it sure made a roaring comeback.

It spread like a murmur in a crowd. It was written in people's complicit smiles. It hovered in a hundred different conversations as folks breathlessly broke the news to their neighbours, who already knew anyway. No matter. Repeating it was a kind of liberation in itself.

The excitement was palpable. "The Americans are here!" was a refrain heard all over town. Everyone knew all the other Allies were landing troops too, but there was a special kind of awe about the Americans because they were so much more "exotic," Dad says.

It would be another couple of months before he would lay eyes on these exotic Americans who had come from so far away.

As the summer progressed, so did Patton's army. The populace was on the knife's edge of anticipation and fear. The liberators were preceded by word of mouth – people knew which cities and towns had fallen into their hands – but no one knew if they'd be skipped over as the Allied high command pursued strategic objectives. And no one knew when and where the feisty Germans might make their next stand.

By the second week of August, the situation in Dad's neck of the woods was chaotic. The Germans had fled Tréguier – the little town where I was to be born two decades later – and they had blown up the bridge. (For reasons no one seems to be clear on, it was called the Canada bridge.)

Self–proclaimed French Resistance fighters filled the vacuum, taking charge of the town. Dad lived up the hill, in a small community called Plouguiel, whose steeple could be spotted for miles around. In a flight of exuberance, a classmate of Dad's climbed the spire and flew the French flag from the top, for all the world to see.

Then the Germans came back. Everyone feared there would be reprisals. During the occupation, hostages had been shot for less. But the Germans were in too much of a rush to care about the tricolour fluttering over the landscape.

"They had run out of time, the poor fellows," Dad says. That note of pity you hear comes from the realization that the German army by then had its fair share of young conscripts – kids not much older than he was and who had no choice but to fight for their country and their lives.

There were skirmishes in the following days, but the inevitable happened on Aug. 14, 1944. U.S. Army jeeps rolled into Tréguier to scenes of jubilation. People had come from all over to cheer them on and girls rushed out to kiss them.

The troops made themselves even more popular by handing out chewing gum to the kids. One boy from Plouguiel got the ultimate prize: A soldier gave him a horse he had taken from the Germans.

"We were so happy to see them," Dad says, "and they, too, were so happy with the reception they got."

There was a language barrier, Dad says, but there was no colour barrier. Most of these 200 or so soldiers were black. It's ironic to think that back in 1940s America, they could never have dreamed of such a show of appreciation from throngs of ecstatic white folks.

Mom's war

Mom remembers the Americans fondly, too. She was in southern Brittany when they finally arrived – armed with chewing gum. The streets were thick with U.S. soldiers, she says, and it was quite a relief. Days before, the Germans had been in a mad scramble and no one knew what was going to happen.

Mom was only nine when war broke out in September 1939. Within days of the opening of hostilities, her town was bombed by the German air force. She lived by a military base and college near Versailles – her father was a chief petty officer in the French armed forces – and they were in the line of fire.

One day, the bombs began falling even as the air raid sirens were still wailing. With no lead time, her family of four still managed to reach the shelter.

Everyone from their apartment building was cowering in the basement when a stray bomb, probably meant for the nearby train station, fell in the courtyard instead. The blast was deafening. The concussion blew the basement door down the stairs, and along with it came a fierce gust of air. What followed was a cacophony of coughing, screaming and crying. Thankfully, the apartment building and its inhabitants survived.

"I pity those who suffer under bombardments nowadays," Mom says wistfully.

She is four years younger than Dad, and for her, the Second World War is more of a jumble of vivid memories. Her family moved around a lot, as her father was transferred from base to base. The two constants were fear and privation.

Her father would save the meat he was served for lunch at the barracks and give it to his children for supper. She remembers the clamour of the street fighting between the French Resistance and the German army in the pocket of Royan, where the enemy held out until April 1945. She remembers her mother concealing her younger brother so he would not be taken as a hostage with other menfolk, as sometimes happened during house–to–house sweeps.

Liberty's legacy

My parents' youth was ruined by the catastrophe of war. Food, clothes, shoes and cigarettes continued to be rationed in France until 1952. Mom and Dad married late, in 1962, and moved to Nova Scotia in 1966 with me and my older brother.

I am not yet 40, but I too am a child of the Second World War. My parents' stories are my stories now.

I have made my pilgrimages to the beaches of Normandy where destinies great and small were played out 60 years ago today. I have crouched before the graves of the fallen, burdened by the knowledge that my generation is the beneficiary of this lopsided bargain of liberty. Never being called upon to put life and limb on the line for what you believe – that is the greatest luxury of all.

I have grown up a global citizen – not so much a patriot of any one country but of the grand alliance of democracies that was born of the Second World War. Still, there are no nations nearer and dearer to my heart than Canada, France and the United States. As it happens, they all have birthdays in July.

But today is another birthday, for a special guy whose name is Guy. He has taught me more than he will ever know about honour, integrity and courage. And he has just turned 78. Happy D–Day, Dad.

Laurent Le Pierrès is Opinions section editor for The Chronicle Herald. His father died in 2013; his mother lives in Halifax.

D-DAY AT 75: Remembering the heroes and sacrifices of Atlantic Canada:

- VIDEO: The road to D-Day

- Why a school in France is named for a Pictou soldier

- U-boat hunter Roderick Deon returns to Juno Beach for D-Day

- Sound of gunfire rang in P.E.I. soldier’s ears

- North Nova Scotia Highlanders at the sharp end of D-Day invasion

- STORY MAP: Follow the D-Day experience of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders

- 12 North Nova Scotia Highlanders murdered at Abbaye d’Ardenne

- ‘It was noisy as the devil,’ says St. John’s torpedo man

- 59th Newfoundland Heavy Regiment was eager to do its part

- A P.E.I. dispatcher’s long, uncertain journey to Normandy

- LAURENT LE PIERRÈS: D-Day invasion was best birthday present for my Dad

- ‘Sight of our boys being blown up ... wouldn’t leave my mind:’ Bedford veteran, author

- Dartmouth veteran's first combat mission was D-Day invasion

- Halifax air gunner had bird’s-eye view of D-Day

- ‘We had everything fired at us but the galley sink’: Yarmouth County veterans share war and D-Day memories

- New Waterford veteran has lived good life after surviving D-Day invasion

- JOHN DeMONT: An old film clip of D-Day shows the nature of courage

- D-Day landing map’s origins a mystery to army museum historians