Last week’s wind and rain storm was quite a doozy; it’s been a while since a weather event caused such a commotion on my Facebook page. I am blessed to have so many followers who have such a keen interest in the weather.

Last Friday, only hours after the clouds cleared, I received an email from Bob Feindel.

On last Friday’s weather page, I said the storm was not a true nor’easter.

Mr. Feindel asked me to elaborate: “… I'm one of the many that don’t see how that is possible if our storms come from the southwest. I was hoping your article would clear things up, but it hasn’t. Perhaps I'm reading too much into trying to understand this, but I feel like your explanation fell short of setting this straight, at least for me.”

Before we go too far, let me remind everyone that first and foremost, a nor’easter is a low-pressure system. In the northern hemisphere, the wind rotates counterclockwise around a low.

Let’s have a look at what makes a storm a nor’easter:

There are two main components to a nor’easter: a Gulf Stream low-pressure system and an arctic high-pressure system. Gulf Stream lows develop off the coast of Florida. Typically, this low would circulate off the southeastern U.S. coast, gathering warm air and moisture from the Atlantic. Strong northeasterly winds at the leading edge of the storm pull it up the east coast.

That’s where the arctic high comes into play. As the strong northeasterly winds pull the storm up the east coast, it meets with cold arctic air blowing down from the north. When the two systems collide, the moisture and cold air produce a mix of precipitation. The resulting precipitation depends on how close you are to the converging point of the two systems.

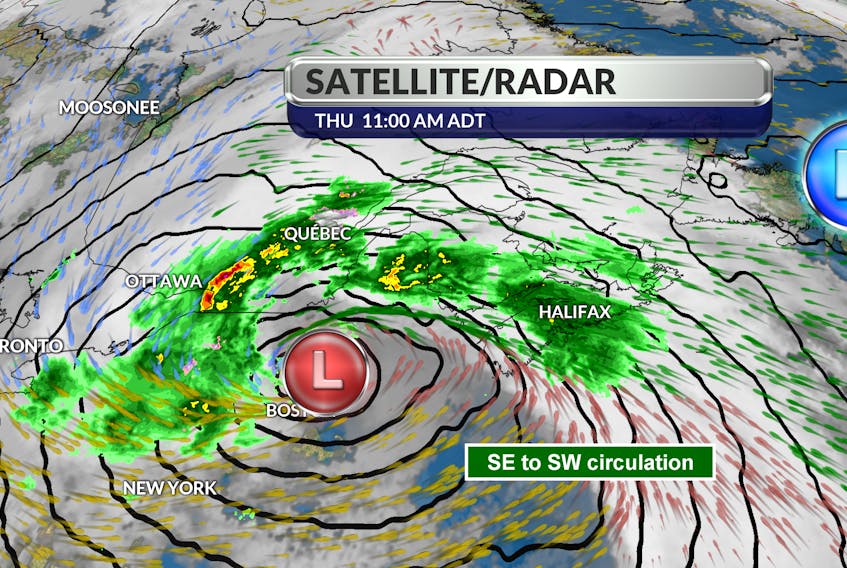

Last week, the arctic high was not in place. There was a stalled high off the east coast of Newfoundland; it forced the storm to track inland, then up and over our region. Our winds blew from the southeast then turned to the southwest. Had the storm been held offshore by a blocking arctic high over Quebec, our wind would have been from the northeast. To be a nor’easter, the predominant wind direction during the height of the event should be from the northeast.

Nor’easters occur along the eastern seaboard any time between October and April when moisture and cold air are plentiful. They often dump heavy amounts of rain and snow, producing hurricane-force winds, and creating high surfs that cause severe beach erosion and coastal flooding.

- Visit your weather site.

- Have a weather question, photo or drawing to share with Cindy Day? Email [email protected]

Cindy Day is the chief meteorologist for SaltWire Network.